About─Deknobo

Poltergeist-type Robot

If the definition of being human is grounded in having a spirit (or a soul), then it goes without saying that human-ness is not defined by its outer shape. No matter how his or her figure might change, the person you love always remains the person you love.

A robot which aims to become human ultimately has to imitate not the outward shape of a human being like dolls, but the form of the human spirit itself which remains unchanged no matter how the appearance changes. We call such a robot, "Poltergeist-type." For instance, if one was deprived of his body and turned into a coffee cup, or a fountain pen, how would he show his presence? Just like usual gestures of a person when using daily belongings inevitably show his character, a disembodied soul should be able to demonstrate his definite presence by wiggling or slightly shifting daily objects.Motion without seeing

The character of a person dwells not so much in the product of handwriting but more in the motion or attitude of the pen that leans, hesitating and revolving at times. Nevertheless, we painters can never see the figure of ourselves painting. This is the very condition that painters and dancers share. Likewise to painters, dancers cannot see the figure of themselves dancing, but quite astonishingly, they are able to create marvelous motions nonetheless.

Motion is not a visual figure. A photograph, for instance, cannot capture the figure of the movement itself. Needless to say, motion is not the picture or the body itself, but rather what connects the picture and the body (which draws or sees).

This is the greatest lesson I learned from Trisha Brown who as well as being a dancer, is an astounding drawing artist. For Trisha, even the motion of her fingers that runs the pen while making up the choreography is already in itself a dance. Thus, the two motions of the dancer and the drawing artist/choreographer belonging to differing space and time are able to encounter on the same stage within the same time.

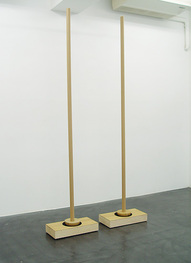

The Care of DekNobo

There is something that moves about the corners of the room, even though it is supposed to be a dead and immovable object. Kafka wrote that this was what caused "The Care of the Family Man," naming the object-creature "Oderadek." A useless person is called "dekunobo" in Japan, which can be translated as "dull (dummy) stick or boy." Kenji Miyazawa (the most important poet of modern Japan) thought that such dekunobo was the true proof of being human.

If an object were a mere tool, we would simply toss it in the trashcan once it becomes useless, like a blunt knife. But we humans are already forgetful even before we know anything; we tend to be capricious and end our lives while continuously breaking down (catching colds very easily). In spite of being such useless objects, we simply never cease to care about ourselves and other people. Therefore, as Miyazawa must have thought, being human is rather grounded in treating what is not yet sufficiently human, in other words a mere object (dekunobo,) as human.

That is why we named our robots "DekNobo." And although we care very much whether the DekNobos look smart or dull, the DekNobos on their side, in spite of being mere sticks, care about everyone else much more than that.

(“DekNobo Says” by Kenjiro Okazaki)